Is it significant if we don’t remember?

Most locals walk past the Allied Trades War Memorial Hospital without a sideways glance. It’s austere beauty slips past their notice. They’ve become so accustomed to its presence that they’ve stopped seeing it.

Most wouldn’t know the history of this heavy brick building’s undulating curves and graceful placement, but does that make it any less significant?

In 1942 Fred Paul, President of the Australian Meat and Allied Trades Federation, lost his son, Sergeant Pilot Frederick Anthony (Tony) Paul in the war. He would not be the only father to lose a son, but he wanted his loss to matter. He heard of the work that Fr Thomas Dunlea was doing at Boys’ Town and felt it befitting to memorialise the lost sons of the war at an institution rehabilitating lost boys.

He and the members of the Meat and Allied Trades Federation decided to build a hospital for the boys at Boys’ Town to memorialise the men in the Meat & Allied Trades who had lost their lives in the war. They raised over $7,000 to build the hospital through fundraisers such as The Ugly Man and Popular Girl Competitions.

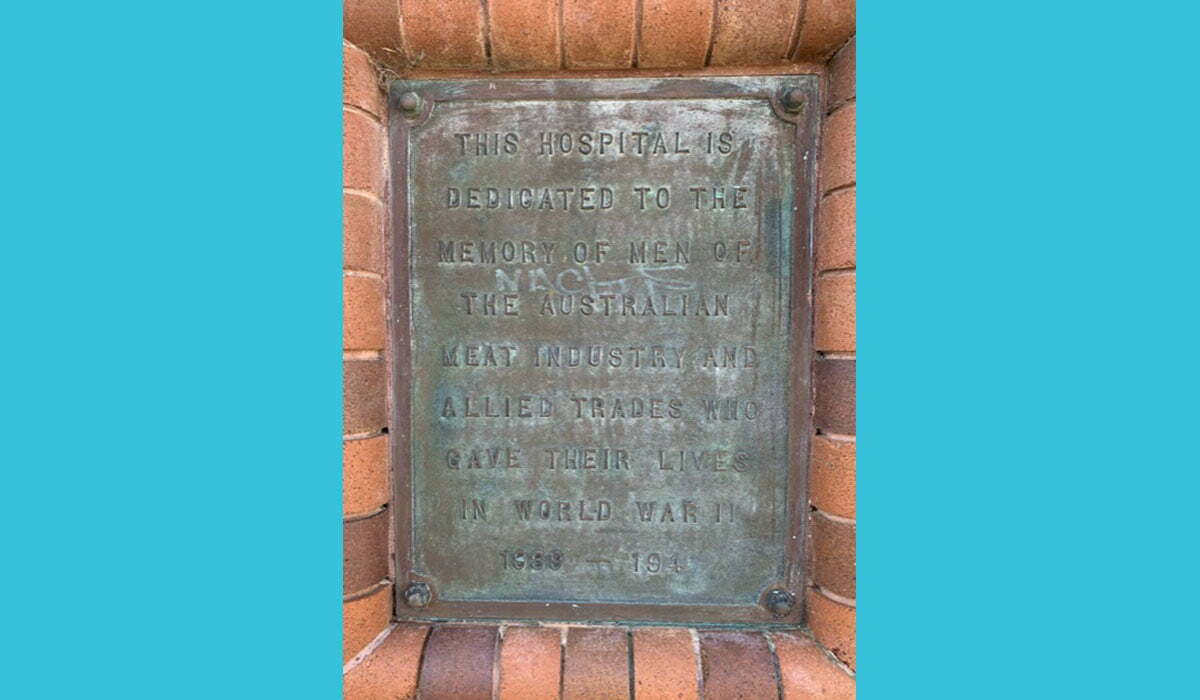

According to the Sydney Morning Herald, “five thousand people” journeyed to Engadine for the hospital’s ground breaking and unveiling of the newly erected Memorial Gates (29 May 1944), including the President of the Sutherland Shire Council, ES Shaw and Councillor Burrell and architect Francis P Ryan and builder W Cruickshank. As the plaques were uncovered, Councillor Shaw read the wording on each of the two plaques. The second (on the right gate post) of which reads:

“This hospital is dedicated to the memory of men of the Australian Meat Industry and Allied Trades who gave their lives in World War II 1939-194.”

The year was left unfinished because the war was still raging when the gates were erected. Two years later after the war had ended and the hospital was finally being opened, it was decided to leave the date unfilled as a reminder that the ravages of war never truly end.

Built on high ground, each of the hospital’s four wards opened onto a veranda, allowing convalescing patients to recuperate amongst the flora and fauna of the surrounding Royal National Park. It was truly ahead of its time, incorporating the “latest ideas on modern hospital construction” including an isolation ward, casualty, operating theatre, dental room, opticians’ room and a room for the latest in imaging–an X-ray machine (Hurstville Propellor, 1 June 1944). On the 19th of May 1946, it opened to great fanfare. The Boys’ Town band played and people from all over New South Wales came to celebrate its opening with Father Dunlea and the boys.

People came from all around to celebrate, not the building, but the communitas that built the building. Money and building resources were in short supply during the war years, but somehow the whole of New South Wales got behind the effort to build this hospital. It became a beacon of hope amidst the daily despair of the war years. Its progress was reported in gazettes and newspapers across the state and further abroad. A hospital memorialising deceased veterans provided hope for wayward and homeless boys, but it also provided hope for a nation struggling with quotidian loss.